The Failings of Simulation Theory

Simulation theory may not be a new idea at all, and it most certainly fails to explain where we ultimately come from.

A New Idea and an Old One

I was daydreaming a while ago, and it occurred to me that there are many parallels between simulation theory and religious theory, and they both seem to answer questions while failing to reasonably answer the ultimate question.

I should start by saying, I am not religious, and this article is not an attempt to threaten anyone’s beliefs. I am simply exploring ideas.

I sincerely enjoy the simulation theory and largely believe it, even though it cannot be proved except through theories of probability (so far).

The theory makes the universe feel a lot less lonely, but it leaves most of my questions unanswered.

In a thought experiment (in my daydream the other day) I entertained the idea that simulation theory was a religious theory with scientific labels. The more I thought about it the more it made sense, but it didn’t totally check out.

The theory could scientifically explain the origins of our universe. The “creator” is merely changed to a “simulator,” and the creator’s infinite, heavenly, unknown domain is redefined as another universe that is unknown to us but entirely scientifically possible.

All of this assuming that in an infinite realm of possibility, the existence of other universes is certain as well as the existence of simulations within them. But this assumption lends credit to religious ideas.

I think it could be argued that the existence of gods or at least the possibility of their existence remains as well. We do not know what other universes are like, we do not know if they are confined by the rules that we understand are fundamental to our existence. Our rules may just be simulated, after all, and totally unique to our universe.

I noticed however that people take the simulation theory a step further. People talk about it as if it can replace religious theory, but it cannot.

The theory limits itself severely to maintain scientific utility. It does not dabble in the question of the ultimate beginning. People don’t notice it, though. They see an answer to the beginning of our own universe and are content with it. The theory cleverly pushes the question of everything’s origin out of the picture by introducing a buffer, the simulator’s universe.

Simulation theory brings what preceded our personal universe into the realm of science, by bumping the original universe outside of the picture, discounting the question of “who made the original universe?”

The Failure of the Simulation Theory

In this way, although they are similar, simulation theory cannot totally replace religious theory. Simulation theory cannot answer the questions that religious theory answers (unless it involves some combination of the two types of theory, in which case it would lose scientific credibility).

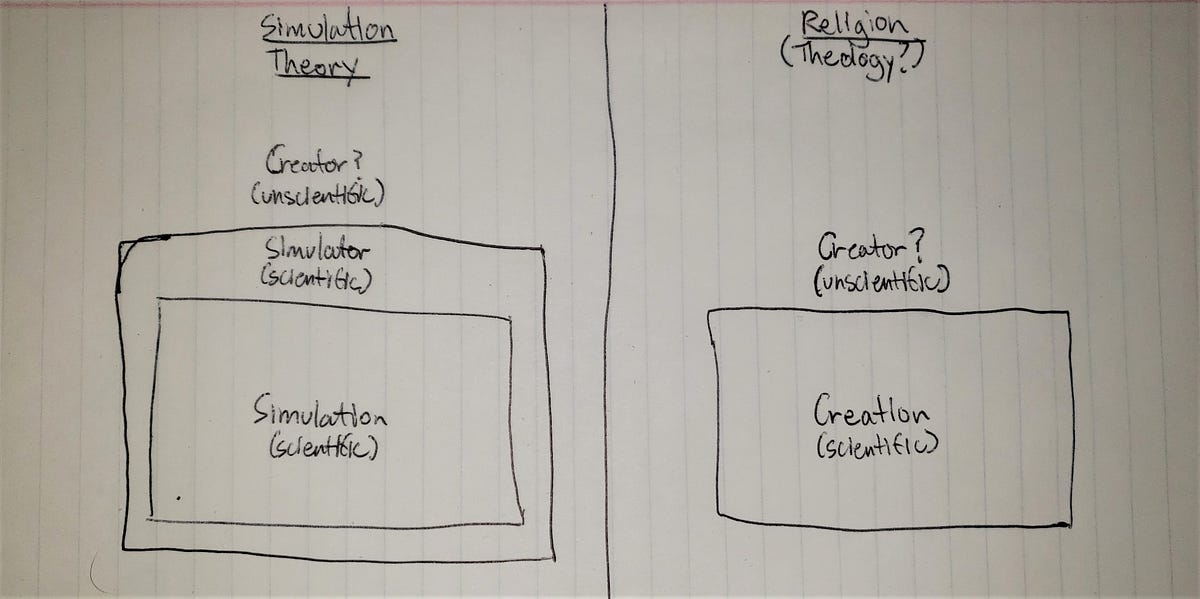

I drew out a comparison: Simulation theory on the left, Religious theory on the right. In the center of each side lies the initial square, our universe. Beyond it lies the unknown. Each side attempts to fill that unknown space with an answer or an explanation.

Simulation theory pushes the question of the universe’s beginning back one step, to another universe in which we have been simulated by something or someone. It creates a buffer universe between us and the question of “God.”

Simulation Theory:

What came before us: ANSWERED

What came before everything: UNANSWERED

If simulation theory attempts to explain what came before our own universe, it has succeeded quite well. If, however, it seeks to explain what came before everything, it fails.

The problem is, essentially, that the theory does not answer the question of anything beyond the beginning of the simulated universes. If we were simulated, who created our simulator and his universe? And who created him, or his simulator, and so on.

The question of the original universe(s) remains. Was there a beginning? Shouldn’t there always have been something, because something cannot arise from nothing? What was there originally?

Are these questions relevant, are they worth asking? Do they have answers that can be understood by humans? I’m not sure that they do.

The Answer to it All

It is only human to seek an answer that satisfies human rationality. All of science has been built in this pursuit. Any answer beyond rational is superstitious and stands on faith, and becomes as good as any other answer of its kind (except to he who has faith, but that is a different discussion).

Scientists focus on what is within their reach, what can be measured and experimented on. But people are not all scientists. People don’t have the time or energy to be preoccupied with these questions, so they often give in to whatever seems most convenient an answer, dismissing any doubts and carrying on with their lives. But the answers such people choose are few and limited, which surprises me and demands explanation.

The Pickle

It seems any theory crafted to explain what was before the beginning of the universe (or in other words, the transcendent) either utterly fails to answer the question or falls in line with religious ideas (unverifiable).

It seems we are stuck in a pickle.

The realm of the transcendent is impossible to observe by its own nature and must be unscientific, but we still attempt to explore it. As soon as the transcendent is defined, it becomes observable, measurable, and finite, both losing its essence and failing to answer the question; what is beyond the finite?

As a consequence of the nature of the question, the answer is left to the human imagination, but every answer the imagination produces is either verifiable and fails by default, or unverifiable and not worth pursuing.

Does the question that either the theory of simulation or religious theory attempts to answer require an understanding beyond the limits of human understanding?

Did that not make sense? A metaphor can better explain what I said and what I’m asking.

Chain Links

Picture a chain, we’ll call it the chain of causation. We seek to know what produced the first chain. Each chain links together with another chain-link before it, all the way back to the big bang, the first link in the chain (or if you’re religious, god’s big bang, which is pretty much the same thing).

Here’s the problem. As soon as you guess what preceded that first chain-link, you merely link the answer on as another link in the chain (i.e., the God link, or the simulation link), pushing the question further into the dark.

The simulation theory puts a whole universe worth of chain-links between us and that terrible, terrible question of what lies beyond it all. I think it’s only natural for the rational mind to take comfort in this huge buffer. Our fear of unknown territory becomes largely satisfied, and yet our first question remains unanswered if we have the courage to admit it to ourselves.

But perhaps it is our humanity that blinds us. Perhaps we expect a primary chain-link, a god-link because we are a chain, existing in this universe filled end to end with chain links. It’s just how a chain would think. It would think in terms of chains. This is why people are disturbed by the question of the transcendent, and why humans have always pretended to have answers.

This must be the line where the “computer program” fails to understand what is beyond the computer, or the line where the creation fails to understand the realm of god.

What a strange question, where did it all come from? Can its answer be known? If it can be known, is it communicable? It is as though a sensible explanation of the true beginning of everything falls short inevitably.

I guess the answer is in the term we seek to define: the transcendent.

As soon as the transcendent is defined, it loses its transcendent quality. If a definition makes sense, it is brought down to the level of the transcended and demands an explanation of its own (i.e., the chain links).

If an explanation exists, it can only be known by one, it is broken down in communication and loses the essence of its truth (it becomes a chain link). Human communication is effective in many ways, but in terms of the abstract and the beyond it fails utterly.

The Religious man, the Atheist, and the Agnostic

This principle is exemplified in the famous argument between the religious man and the atheist.

The religious man says, “Atheist, how could you believe that there was nothing before the beginning? Someone must have created us, for we exist!”

The atheist replies, “Well if you’re saying god made us, then someone must have made him, for he exists!”

The atheist and the religious man do not realize it, but they do agree on one thing, what exists demands an explanation. The atheist claims nothing before man, and the religious man claims nothing before god.

And here we see the logical fallacy inherent to the atheist’s argument.

The Blind Atheist

The atheist claims that nothing existed before the creation while insisting that if god existed, something must have existed before him. But why not nothing, as he already believes? He’ll say there was nothing before our universe, and that he is sure of it.

This is why I am agnostic, I do not insist on knowing what was before, like the religious man and the atheist.

The religious man sees the darkness beyond the borders of our knowledge and is afraid, so he believes there to be a god. He fills the darkness and vanquishes his fear.

The atheist, alternatively, sees the abyss beyond the borders of our knowledge and is afraid, so he denies that anything beyond it may exist. He sustains himself by mocking the insufficient image of a man-made god while hiding his own fear behind a veil of denial. He claims that he is a scientist and a rationalist, but he fails to understand that beyond the limits of science there is still the unknown, that which he denies.

The religious man should ask him, “Atheist, was there cancer before radiation was observed? Did the birds not fly before the Wright brothers built their flying machines? Has the earth not always orbited the sun, before we knew it? Was the speed of light any slower before it was measured? How can you say that there is nothing beyond what you know?”

The atheist prides himself on his rationalism, but he insists that he knows what cannot be known, the ultimate unknown. He insists there is nothing beyond our universe when there may be something after all. The atheist is Achilles, the indestructible rationalist, but he fails to cover his heel and believes what he does not know.

The atheist does not care to know what is beyond, he busies himself with his life and silences his own curiosity. The atheist knows that questions can be monsters, he does not care to wander into the unknown.

The Agnostic

This is where agnosticism succeeds, but only barely. The agnosticism lays no claim to a belief that is correct. He is only not yet wrong, and that’s something. Every religious and atheistic person must first be an agnostic and in being one are not yet wrong. But I am an agnostic, I cannot say that I know they are wrong, only that it seems unlikely that their explanation is sufficient.

Picture a ship.

The religious man warms himself in the cabin and is dry, reading his holy text by the light of his lantern. The atheist sleeps below the deck, not bothering to wake until called.

The agnostic, however, climbs to the crow’s nest. His eyes may burn from the salt and the wind of the stormy sea, but he keeps them open always. He may grow tired as he waits day and night, wary of the expanse of air around him and beneath him. But he knows that if ever something is to be seen that was not seen before or something to be known that was before unknown, he will be there to see it and to know it first.

In Conclusion

Simulation theory shows that although we may think we are making progress forward, our path forms a circular road, leading back to the beginning, the question of meaning.

Simulation theory and the theory of god are the same in that they are theories of mankind. Our humanity limits us but also lends us our identity, the lens through which we understand.

We are like water in a clay pot, limited by the bounds of our human form. But we are shapeless, nothing without our strange humanity.

We must continue on our journey, following the shape of our nature while pushing its bounds. We shouldn’t resent the limits and strains of our humanity but engage with it, explore it, allow it to speak to us. As it was famously said by Carl Jung, “If you think along the lines of Nature then you think properly” (that quote is often taken out of context and can be easily misinterpreted, I hope I haven’t misinterpreted it here. To explore the context of the quote, click to view the segment of the interview in which it is said).

We must not forget to maintain doubt. Doubt is an open door for the mind. As soon as we close it we deny the existence of truth beyond ourselves and become willingly ignorant.

When we encounter those who believe differently than us, we must not dismiss them. A failure to produce evidence does not mean that there is none. It may be possible that there is evidence that cannot be communicated, many people make that claim. It is ignorant to deny this possibility.

We should not be afraid of what we do not know, it is what we do not know that characterizes what we do know. It is what makes us who we are, it is our limits that define us to make us human, as the fragile walls of the clay pot lend the water its form.

Without our limits we would be unlimited, we would be gods, everything and nothing at the same time, undefinable, the transcendent.

Perhaps the answer to the ultimate question lies in our asking of it. We are the transcended, ever seeking to know the transcendent from which we came, and yet the transcendent produced us to know itself, driven by some curiosity.

Perhaps that is what we are. Perhaps we are god’s broken mirror, shards of the transcendent that broke itself down so that it could know itself. Perhaps god was lonely, perhaps the infinite was empty, perhaps the finite is what makes it all worth it.

Is it an infinite struggle, or an infinite dance, between us and god? It depends on who you ask, and if you ask me, it need not always be a struggle.

p.s. I do not mean any particular god when I say, god. I only mean what the idea of god was originally made to represent. Thanks for reading.